The Abundance Debate We’re Not Having

To shift American politics onto more productive grounds, the abundance agenda needs a broader cross-ideological debate than critics or advocates alike have allowed.

The best way to read Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book is to take the authors at their word. Abundance is what is usually called a “policy book,” but Klein and Thompson don’t quite offer a traditional policy agenda. Instead, the authors begin and end with a question that is also a concentrating lens. “Can we solve our problems with supply?” More broadly, if we focused our attention on expanding the provision of goods and services rather than fighting over who gets what, or who is winning or losing the culture wars, what might we learn?

The central problem of American politics, Klein and Thompson imply, is not conflict but the scarcity that fuels it. If we lived in a world of real material abundance—for example, where people had sufficient access to housing and the other resources necessary for a good life rather than just consumer goods—people would be less dissatisfied.

Such abundance might provide an indirect response to Klein’s previous book on political polarization. The best way to solve America’s political polarization, the book slyly hints, might be to side-step it: to shift American politics onto new grounds of debate about new topics where political disagreement might even turn out to be productive. If we are all fighting over the best way to increase the supply of things that everyone wants to have, we’re more likely to discover solutions that make everyone better off.

Abundance has little explicit to say about democratic contestation and the gaining and losing of power. The book invokes the importance of the public interest without properly explaining how to figure out what that is.

Unsurprisingly, that is not the spirit in which many have interpreted the book. Some centrists—who believe that the left made Democrats lose the 2024 election—have deployed the abundance agenda as a cudgel to batter their ideological enemies. Some leftists see abundance as a stalking horse for a neoliberalism that systematically ignores the problematic concentration of power and influence in favor of arid technocracy.

It is easy to project because Abundance has little explicit to say about democratic contestation and the gaining and losing of power. The book invokes the importance of the public interest (as opposed to the manifold interests of groups) without properly explaining how to figure out what that is. Self-interested groups can—as Klein and Thompson argue—gum up policy through imposing layer after layer of requirements. Equally, however, it’s impossible to figure out even the roughest notion of what the public good might be without organized contention among interests.

Because of this omission, two somewhat different kinds of argument get jumbled together: the general claims for abundance, which a lot of people might agree is a good thing, and proposals about the specific ways we might get there, which are more likely to provoke dissent. The first involves the point that liberals (and, by implication, leftists, moderates, and conservatives too) ought to focus on abundance as their goal. The second is Klein and Thompson’s more particular diagnosis of what has gone wrong with American politics and how to set it right. The two are distinct. You can believe in the first without the second, and even accept much of the second without the first. You might, for example, dislike the politics of zoning laws without anticipating that getting rid of them would help open the floodgates of prosperity.

I imagine that Klein and Thompson, like the rest of us, believe that they are absolutely right on their particular analysis of what has gone bad and how to fix it. Equally, I think that they’d count it as a victory if people start arguing with that diagnosis and proposing their own alternative paths toward abundance. Long-term political success is often less about winning a particular fight than shaping the ground and stakes of future contestation.

That is why a second question lurks behind Klein and Thompson’s query about solving problems over supply. What would political disagreements look like if they were fights over how best to achieve abundance?

As it happens, Klein and Thompson’s project is in part the product of such arguments. Just a few years ago, many conservatives and libertarians seemed to want to talk seriously about the relationship of governments to markets in producing abundance. Far to one side of this debate, socialists were engaging in their own internal discussions over whether a state-planned economy could produce abundance without capitalism.

To understand the future of abundance, it might be useful to look back to its past. What were the ideas that people were arguing over? What did they get right, and what did they leave out? Like many books with a clear sweeping claim, Abundance emerged from the murk and confusion of a less organized previous debate. Recapturing a little of that debate’s variety could help us see what we can get out of the book, as it begins to generate its own fruitful disagreements. The abundance agenda is becoming increasingly central to liberals’ aspirations for building a post-Trump America. If Trump’s project fails, abundance may become the center of a much bigger cross-ideological debate as everyone begins arguing over how to build something better amidst the wreckage. We ought to start thinking about how that debate ought to be grounded.

More than one review of Abundance has suggested that it was written for an America in which the Democrats won in November 2024 and hastily retrofitted for the future that actually happened. That might or might not be true. The bigger truth is that Abundance emerged from a vigorous debate in the early 2020s, which treated California as a synecdoche for the problems of America.

That debate was naturally dominated by Californians. In particular, many people who lived in or near San Francisco agreed that something had gone very badly wrong in a city that had hit the magical trifecta of public squalor, political stagnation, and gross economic inequality. Some blamed the tech industry for what had happened. Those within tech or adjacent to it focused on the political roadblocks that local interests had built to stop anything getting done. Most obviously, it was extremely difficult to build anything new.

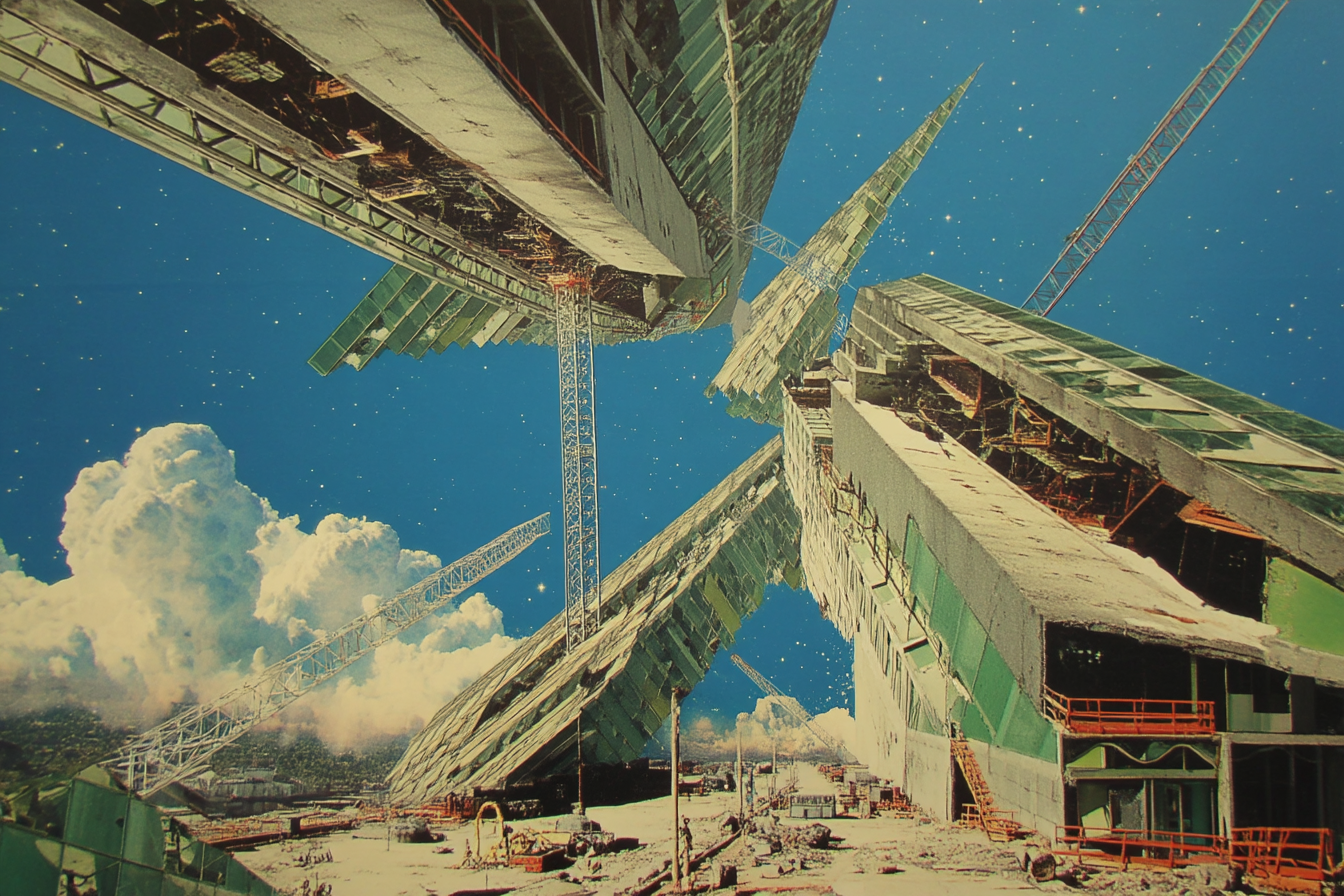

Two prominent diagnoses came out of this latter debate. Marc Andreessen, a venture capitalist most famous for predicting that software would eat the world, announced in 2020 that the policy failures of coronavirus meant that it was “time to build.” Not only did America need to start producing all the things that were in short supply during the pandemic; it had to start building cities, factories, and transport systems, as it once had. According to Andreessen, the main obstacles to this were lack of imagination and regulatory capture. Rebuilding America would require both right and left to change how they thought about the world. The right would have to conquer its tendencies to crony capitalism and cozy oligopolies and allow markets to do their work. The left, meanwhile, would have to show that government could work, building hospitals and schools and committing “the public sector fully to the future.”

A little later, Klein began writing articles arguing that America needed a “liberalism that builds” and that was willing to recognize how much its addiction to process and procedure got in the way of doing what needed to be done. For example, Klein argued that the spiraling costs of building housing and infrastructure in the Bay Area stemmed in large part from well-meaning regulations like the California Environmental Quality Act, which provided the opponents of change with the tools they needed to stymie or stop development.

Klein’s position certainly wasn’t derivative of Andreessen’s, or even a direct response to it. It would be more accurate to say that both Andreessen’s and Klein’s arguments drew on broader thinking in the Bay Area, involving many less well-known people in online and offline discussion groups. Klein also drew on other sources, such as Aaron Bastani’s arguments for “Fully Automated Luxury Communism.” Why couldn’t liberals have their own wildly utopian ambitions for material prosperity?

It seemed in late 2022 and early 2023 that something new might be emerging. Bay Area liberals and libertarians were both urgently interested in escaping the California trap and achieving material abundance. Then the conversation turned sour.

Andreessen, who had been stewing in an increasingly toxic mélange of far-right online sources and books, was also angry at the people who wanted to slow down AI in the name of safety. His various frustrations boiled over into a so-called “Techno-Optimist Manifesto,” which made common cause between Silicon Valley and the reactionary right, harking back to fascist ideologues like the Italian futurist Filippo Marinetti. Calls for safe AI, the manifesto argued, were tantamount to the murder of all those people whose lives would be saved by new technology. Making common cause with liberals would prevent the radical disruption that Andreessen believed was called for, in which DEI, ESG, and all the other enemies of innovation and progress would be utterly destroyed. No one was particularly surprised when Andreessen eventually endorsed the presidential campaign of the greatest crony capitalist of them all, Donald J. Trump.

To liberals like Klein, this was not the apotheosis of progress but its betrayal. In a caustic essay for the New York Times, Klein acknowledged that some of Andreessen’s goals were similar to his own, but denounced his means of getting there as a poisonous “reactionary futurism.” Spurring innovation and progress did not, actually, mean burning down government and the left.

The radicalization of the Silicon Valley right had consequences. The promised debate over the merits of markets and government in promoting abundance was stillborn. Abundance’s index skips straight from “Anbinder, Jacob” to “Anthropic.” It briefly mentions parallel efforts to build abundance on the right, but eschews direct engagement.

The timeline where the Silicon Valley right did not go toxic would likely look very different. On the one hand, the movement for abundance would have had more people who were unabashedly right wing. On the other, it would have been forced to debate the actual merits of government versus markets. Instead, at least for the moment, it is an alliance of a select group of liberals with centrists and right-leaning moderates. These abundance advocates mostly focus their energies and attentions on highlighting the problems of a particular flavor of liberalism and providing possible alternatives. This is useful work: there is a lot that is wrong with procedural liberalism. But if that were the only contribution of Abundance, it would be an enormous shame. Actually figuring out the problems that America faces will require more ideas than those that will be generated in disputes between the center and the center-left.

Most responses to Abundance have either praised or deplored its attacks on procedural liberalism. The book argues against the proponents of “a liberalism that changed the world through the writing of new rules and the moving about of money.” Klein and Thompson suggest that such liberals, who aim to turn America into a fantasy Denmark, ignore and even contribute to the general sclerosis of groups and vetoes that are clogging the arteries of America’s institutions.

Building on the late Mancur Olson’s ideas about the rise and decline of nations, Klein and Thompson argue that America has been occupied by groups who get their narrow way by blocking changes in the broader public interest. As a result, America has degenerated into a nearly unnavigable tangle of rules and constraints that breeds further complexity as reform efforts are larded on top of the very institutions they’re supposed to fix. Klein and Thompson say that “a complex society begins to reward those who can best navigate complexity.” Indeed, they suggest that it rewards those who best generate complexity too.

It’s no surprise then that the book has gotten up many left-liberals’ noses: It was written to pick a fight. Equally, it is a great pity that leftists like Malcolm Harris denounce it as a “half-hearted” neo-neoliberal tract, while Kate Willett suggests that Marc Andreessen and his friends will leap out of Klein and Thompson’s intellectual Trojan Horse as soon as it is heaved inside the city walls. In actuality, the book’s extended argument is that we need government to help build a better future, but government must be transformed if it is to do its job properly.

Such disagreements and particular policy proposals have taken up most of the oxygen of debate. There is far less attention to the book’s deeper and simpler core argument that liberals should pay more attention to progress than to process. This is surprising, since the book’s vision of the future is arguably its most attractive part.

That vision is not to be found in the rather static description in the first few pages of how the abundance agenda might unlock a material cornucopia of sustainable energy production, vertical farms, and personal drone deliveries. Instead, it emerges as a byproduct of the main narrative: a future where the buzz and liveliness of great cities become accessible to everyone, where people learn again through the making of things, and where political energies focus on fostering invention rather than manipulating rules for marginal wins. That Tocquevillian spirit of democracy by doing, of an America where collective and individual enterprise reinforce each other and everyone is better off for it, explains a large part of the book’s resonance. We need a lively and attractive future.

While Klein and Thompson have plenty to say about the interests that are preventing the future from happening, they’re much less specific about the interests that might help it prevail.

Klein and Thompson’s most damning condemnation of actually-existing liberalism is that it is profoundly risk-averse, unwilling to clamber out of the deep grooves that it has worn into the polity to discover new possibilities. But that isn’t—or shouldn’t be—just a criticism of liberals. It speaks to a far more general malaise, a dearth of usable futures that could help orient and guide our present.

As many of Klein and Thompson’s center-left critics have pointed out, building a future also involves building a political economy of interests that will make the vision possible, and sustainable over time. Some, like Paul Glastris and Nate Weisberg, suggest this is Abundance’s fatal flaw. Others, like Elizabeth Wilkins and Mike Konczal, see it as a solvable problem. While Klein and Thompson have plenty to say about the interests that are preventing the future from happening, they’re much less specific about the interests that might help it prevail. As some of their critics suggest, forceful actions against monopoly, along the lines pushed by Elizabeth Warren, might be a good start.

Such measures might be less foreign to Klein and Thompson than their detractors think. Warren’s ideas too may owe a debt to Mancur Olson. Equally, it may be necessary to go much further. After software eats the world, what comes out the other end? Perhaps, as Catherine Bracy’s new book suggests, we need to consider whether venture capital makes it harder, rather than easier, to get to the future that we want. Alternatively, as Daniel Davies suggests, we ought to worry less about NIMBYs and more about the weird cybernetic feedback loops through which bad decisions emerge without anyone seeming to have really made them.

Klein and Thompson might very reasonably retort that they could never possibly have fit the whole complex debate about how to improve people’s lives and make good things into a single book, and they would be absolutely right. But even if their book can’t encompass such an argument, it should absolutely get it going. The project of abundance had its beginnings in a fight that was broader than disputes between centrist and left-leaning liberals. It will perhaps have its greatest value in getting an even bigger debate started on sound footing, creating a genuinely dynamic argument about how to build a genuinely dynamic future.